It won’t come as a surprise to some of you, but the history of the DSM is a favorite topic of mine. Of particular interest, is the evolution of how autism has historically been diagnosed to its inclusion in the DSM-5-TR. I thought I’d share a little of my DSM joy.

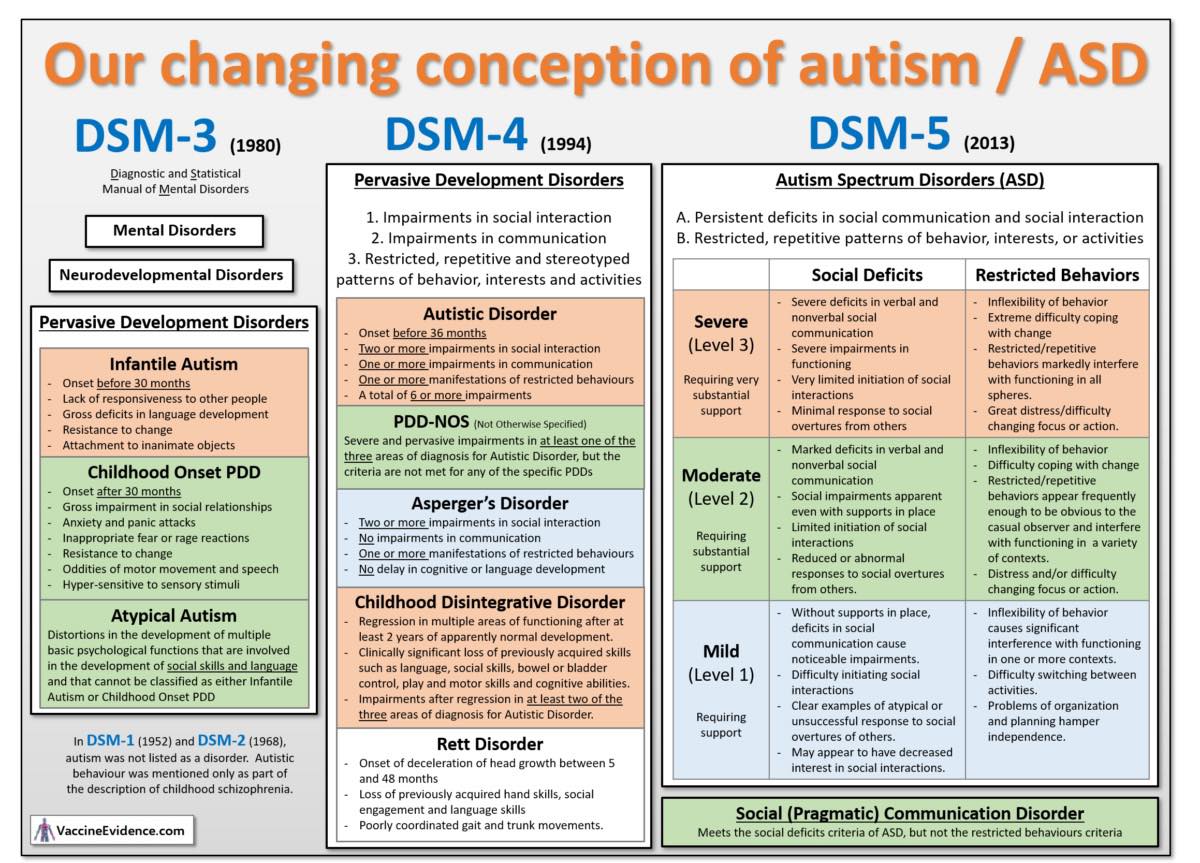

Autism, otherwise known as Autistic Disorder, staked its claim in the DSM III in 1980 (ADHD was also included at this time, focusing mostly on hyperactivity). At that time, it defined severe forms of the disorder with significant social and language impairments as primary features. The criteria were pretty limited and narrow, which resulted in the exclusion of milder forms of the disorder. This explains why your pediatrician probably did not identify autistic traits in you when you were a child.

The DSM III-R came about in 1987, and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) were added to the mix. This was a kind of umbrella term for neurodevelopmental disorders (starting in childhood and being present throughout an individual’s lifespan). This change still placed a lot of emphasis on severe presentations of social and language differences and repetitive behaviors. What were the PDD’s? Rett’s Disorder, Autistic Disorder, and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder to name a few. This was the first attempt to classify a category of developmental disorders.

In 1994, the DSM IV added Asperger’s Disorder to the PDD category. It maintained autistic disorder as a more severe form of the disorder, and sought to present a milder form of the disorder without language impairments and generally with average or above average IQ being seen. Some liked to think of this as autism light. Three domains were include though to make up the diagnosis: 1. Social Impairments, 2. Communication Impairments, and 3. Repetitive and Restrictive behaviors. The DSM IV-TR didn’t change the PDD category.

In 2013, the DSM-5 (note no longer roman numerals) turned autism on it’s head. Previous diagnoses of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and PDD-NOS (DSM IV) were brought into a single category: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The result was a sudden increase in the rate of autism diagnoses leaving some to speculate that the disorder had become over-diagnosed instead of acknowledging the new continuum of the disorder. Asperger’s disorder was eliminated due to view that autism in fact is seen on a spectrum which means that there is no need for a lighter version of the disorder. Instead, the DSM-5 brought in severity levels, again acknowledging the continuum of the disorder.

There were two domains for the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder now: 1. Social Communication and 2. Restricted and Repetitive Patterns of Behavior. These included:

-

Repetitive motor movements: Hand-flapping, rocking, or other repetitive body movements.

-

Insistence on sameness: Strong preference for routines and resistance to change in daily activities, such as eating the same food or following the same schedule.

-

Highly restricted interests: Intense focus on specific topics, hobbies, or activities (for example, a deep interest in trains, numbers, or maps).

-

Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input: Over- or under-sensitivity to sounds, textures, lights, or other sensory experiences.

Symptoms were deemed to begin in childhood and be impairing.

When the DSM-5-TR came onto the scene, the two domains were upheld. There was more of an emphasis placed on cultural factors related to the disorder as well as updates about prevalence rates. Interestingly, rates of autism were diagnosed in 1:2000 to 1: 1500 children under the auspices of the DSM III. Now, the rates are hovering around 1:43. There are definitely criticisms related to overdiagnosis of the disorder.

Tangential Moment: The DSM-5 is no longer in roman numerals because researchers wanted to make it seem more modern and scientific, which if you know me you know I don’t think the DSM’s are. But that’s a sticky wicket for another day.